Two JPL spacecraft are about to exit our solar system, and like dutiful offspring, they phone home every day.

In 1977, JPL launched Voyager 1 and

Voyager 2 to explore the outer planets and beyond. Now, 35 years later,

the two spacecraft are still going strong, far beyond the outermost

planet, Neptune and even poor demoted Pluto. In fact, the two Voyagers

are much farther from Earth than any other spacecraft has ever been —

boldly going where no human creation has gone before, to paraphrase Star

Trek.

Caltech Professor Ed Stone, who served as Director of JPL from 1991 to

2001, has been Voyager’s Principal Investigator since 1972, five years

before launch. Stone, now 76, spoke at a recent Caltech seminar,

bringing an enthusiastic audience up to date on his 40-year-long

project.

The Voyagers explored the outer planets, their magnetic fields, and 48

of their moons. They discovered the ice-covered surface of Europa and

our solar system’s most active volcanoes on Io. They found that Saturn’s

rings are 200,000 times thinner than their width, analyzed the dense

hydrocarbon atmosphere of Titan, and imaged the rings of Uranus and

Neptune. While passing Jupiter, Voyagers survived radiation levels 1000

times the lethal dose for humans.

Voyager 2 arrived at Neptune within 62 miles of its target, equivalent

to sinking a golf ball from 4 billion yards, with some mid-course

corrections provided by small thrusters that deliver only a 3-ounce

force. That’s enough to accelerate a car from 0 to 60 mph in 12 hours

flat. But its fuel efficiency is outstanding: launched with nearly 700

tons of rocket fuel, Voyager 2 achieved 30,000 mpg, while traveling 4.4

billion miles to Neptune.

Voyager 1 is now 123 AU from Earth, moving 3.6 AU per year. Earth’s

distance from the Sun is 1 AU, so 123 AU equals 11 billion miles. After

passing Saturn in 1980, Voyager 1 turned “north” and is rising above the

plane of our solar system. Voyager 2 passed Uranus in 1986 and Neptune

in 1989, then turned “south”, and is now 100 AU from Earth, moving 3.3

AU per year, as illustrated below.

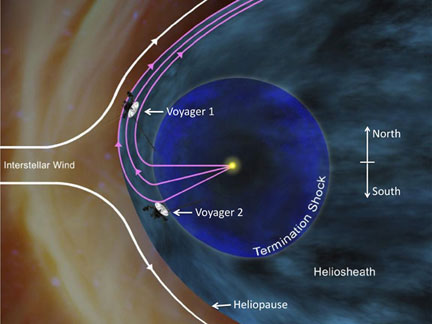

NASA illustration of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 flight paths as they approach the heliopause,

the end of our Sun’s dominance.

In December 2004 at 94 AU, Voyager 1 passed the “termination shock”,

where the solar wind’s speed drops from 900,000 mph to 250,000 mph.

Voyager 2 passed the termination shock in August 2007 at 84 AU. Both are

now en route to the “heliopause”, generally considered the edge of our

solar system and the start of interstellar space. The heliopause is the

limit of the dominion of our Sun’s magnetic field and solar wind, where

its magnetic field changes direction and the solar wind stops. Its shape

is an oblong due to the Sun’s motion through the surrounding

interstellar gas.

Each Voyager records the magnetic fields, solar wind, and cosmic ray

levels around it, and reports back to JPL’s Deep Space Network (DSN) at

160 bits/sec. With antennas up to 230 feet across and located around the

world, DSN’s sensitivity is truly amazing. Voyager transmits at 23

watts, but when their signals reach Earth they are nearly a billion,

billion times weaker. Like some offspring, JPL’s Voyagers call home

collect.

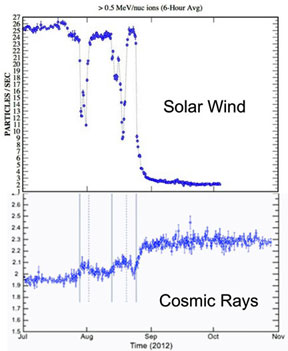

Just announced this month, Voyager discovered something completely

unexpected: a region dubbed the “magnetic highway” that allows

low-energy particles of the solar wind to escape and high-energy

particles from interstellar space to enter our solar system. Charts of

the changing particle counts are shown below. Stone said: “We believe

this is the last leg of our journey to interstellar space."

Voyagers’ computers, which were

state-of-the-art in the early 1970’s, boast 12,000 bytes of memory and

tape cassette for data storage. Electronics and instrument heaters are

powered by radioactive Plutonium. Despite shutting down non-critical

equipment, the Voyagers will exhaust their power and thruster fuel by

about 2025. Except for these consumables, they might have been able to

call home for another century or two.

After leaving our solar system, the Voyagers will fly by other stars.

In 40,000 years, Voyager 1 will be “only” 10 trillion miles from a star

in the constellation of Camelopardalis. In 300,000 years, Voyager 2 will

pass 25 trillion miles from Sirius, the brightest star in our sky.

The Voyagers are destined—perhaps eternally—to wander the Milky Way.

Both carry a greeting for any aliens they might encounter, written on a

12-inch gold-plated copper disk. A committee chaired by Carl Sagan

assembled 115 images, a variety of natural sounds, musical selections

from different cultures, and oral greetings in 55 languages, all

portraying the diversity of life on Earth.

Funded by NASA and managed by Caltech, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

(JPL) is unquestionably the world leader in space exploration. JPL has a

long history of outstanding achievements, beginning in 1936 with

Caltech’s first rocketry projects. Most recently, JPL dazzled the world

with the amazing landing of Curiosity on Mars.

Best Regards,

Robert

Dec 11, 2012

Note: Previous newsletters can be found on my website

|