|

Odd connections exist between science and other human endeavors. Our May 2020 newsletter explored the competition between physicists and archaeologists for lead recovered from ancient shipwrecks.

A recent astrophysics paper by Emil Khalisi of the University of Heidelberg employs astronomy to date the fall of Babylon over 4000 years ago.

Khalisi says the Sumerians are one of the earliest societies whose recorded histories survive to the present day. Their mathematics, based on the number 60, still determines how we measure angles and divide hours into minutes and seconds. Their writing, cuneiform, consisted of wedge shapes impressed in clay tablets.

The Sun, Moon, and Venus were considered gods, whose motions were carefully documented and studied for omens of future successes and tragedies. One such record is the Venus Tablet that documents the risings and settings of Venus over a 21-year span.

The history of these peoples, like the history of all mankind, is replete with tales of one regime conquering another. Perhaps persistent aggression is inherent in our DNA, a result of the Darwinian imperative to propagate our DNA rather than theirs.

For historians, the Hittite conquest of Babylon was a particularly pivotal event, whose date is uncomfortably uncertain. Our chronological evidence is comprised of documents, radiocarbon dating, lists of royal lineage, and, of most interest to me, astronomical sightings. All this evidence is fragmentary, indecisive, and self-contradictory — after all, to err is human, both then and now.

Four major attempts to rationalize this evidence set the sacking of Babylon at 1651, 1595, 1531 and 1499 BCE.

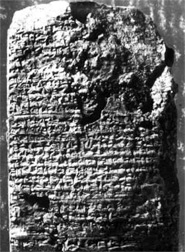

Khalisi’s analysis starts with a clay tablet (ID# EAE 20), shown here, saying Babylon was sacked shortly after an eclipse of the Moon was followed 14 days later by an eclipse of the Sun. This occurred during the Babylonian month of Shabattu, which would be in our winter. We can’t be more precise because the Babylonian calendar was based on 12 lunar months (about 28 days each) per year, and an occasional 13th month. We have no record of when “leap months” were added.

Modern astronomers can precisely calculate where and when lunar and solar eclipses occur, but only if they occur in the past few centuries or the next few centuries. However, for many centuries from now, either way, the calculations are uncertain due to Earth’s changing rotational speed.

We’ve all been told Earth turns once every 24 hours. Actually, Earth’s rotation has been slowing down since the formation of our Moon, billions of years ago, due to drag from the Moon’s tidal forces.

The international standard (SI) second is officially defined as the average period of Earth’s rotation from the years 1750 to 1892, divided by 86,400 (24 hours times 60 minutes/hour times 60 seconds/minute). The average period of Earth’s rotation is now about 0.001 seconds longer.

The Moon’s tidal forces are consistent and slowly waning over billions of years. They slow Earth’s rotation by changing its angular momentum L: L=Iω2, where I is Earth’s moment of inertia, and ω is its rotation rate.

Earth’s rotation is also affected by random events that change I, which equals Mr2, the sum of each of Earth’s particle’s mass times the square of its distance from Earth’s rotational axis. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, for example, shifted a tectonic plate downward, reducing r2, and thus I. To conserve L, ω increased, shortening our day by 3 microseconds. Conversely, China’s Three Gorges Dam raised the elevation of its stored water, lengthening our day by 0.06 microseconds.

Khalisi’s best estimate is that the time of an ancient eclipse must be advanced by 32 x2 seconds, where x is the number of centuries before the year 1800 AD. For the period of interest, the time correction is 14 hours with an uncertainty due to random events of ± 74 minutes.

With all that, Khalisi suggests the solar eclipse mentioned in the clay tablet actually occurred at noon on June 29, 2159 BCE, a much earlier date than previously estimated. His calculated eclipse path is shown below.

I find it amusing that scientists can identify (at least tentatively) a specific moment in time thousands of years ago.

Best Regards,

Robert

August 2020

Note: Previous newsletters can be found on my website.

|