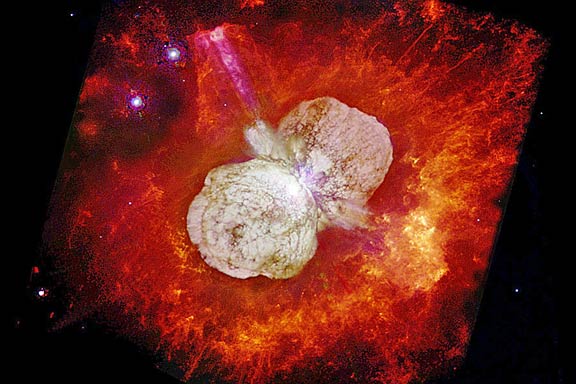

Eta Carinae is one of our Milky Way

galaxy’s most massive, most luminous, and most bizarre stars. Well,

actually, it is a binary system of two very massive stars; one contains

over 100 times, and the other about 30 times, our Sun’s mass. These two

stars release 5 million times more light energy than our Sun, and

are one of the 20 most massive stars in our galaxy. Below is a

recent Hubble space telescope image of the environs of Eta Carinae. What

we see is a vast nebula, 20 times more massive than our Sun, spanning

about 3 trillion miles. All this is gas ejected by the massive star that

lies hidden within.

From 1837 to 1858, Eta Carinae exploded

spectacularly, peaking in 1843 to become the second brightest star in

our night sky after Sirius. (Sirius seemed brighter only because it is

about 900 times closer to Earth.) Unfortunately, this remarkable event

occurred before cameras and modern telescopes existed; we have only

notes taken by astronomers who used the much smaller telescopes of that

period.

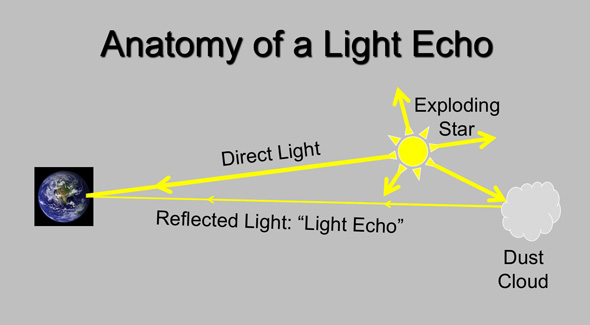

If you happened to miss the action 170

years ago, don’t worry. We can now seeing cosmic reruns due to “light

echoes.” The image below illustrates how this is possible.

Eta Carinae exploded in about 5660 BC, at

a distance of 7500 light-years from Earth. Recall that one light-year

is the distance that light travels in one year. Hence, light from that

explosion took 7500 years to reach Earth, arriving 170 years ago. But

the light spread out in all directions. Some of that light hit a large

dust cloud and was reflected, and some of that reflected light headed

toward Earth. Astronomers call the reflected light a “light echo.” The

reflected light took a longer path to reach us, traveling first to the

dust cloud and then onward to Earth, It thus took more time to reach us

than did the direct light beam. In fact, the path of the reflected light

was 1000 trillion miles longer so it took an extra 170 years to get

here, arriving just recently.

The left side of the image below shows

the Carinae Nebula, with Eta Carinae near the top and the position of

the dust cloud in the boxed area below. On the right side are three

close-up pictures of the dust cloud taken on: March 10, 2003; May 10,

2010; and Feb. 6, 2011. The dust cloud images show progressive

brightening as the explosion intensified 7670 years ago. We are now

watching (for the second time) the explosion proceeding as if in real

time. In reality, what we see is delayed by the travel time of light

across vast cosmic distances. We are seeing the past unfolding in our

telescopes.

The Eta Carinae explosion was quite

unusual in that it extended over 20 years and was not a true supernova,

as one might expect from such a massive star. Indeed, the changes in

light intensity that astronomers now observe in the reflected light

match the light intensity changes recorded by astronomers who observed

the original blast 170 years ago. Based on that, we can expect more big

“burps”.

In the longer term, Eta Carinae is a

prime candidate to become a supernova or even a hypernova, explosions

that would make the 1840’s event look like a hiccup. That prior

explosion is just the rumbling of an unstable, immense star in the death

throes, preceding its final catastrophic explosion. Astronomers expect

that final explosion to occur anytime between next Tuesday and a million

years from now.

We haven’t had a good supernova in our

galaxy for 400 years. We are long over due, but it might be nicer if it

were a bit farther away. At 7500 light-years, life on Earth will

probably not be imperiled. The greatest danger at this distance would be

from a gamma ray burst, but these narrow beams of immense energy

typically shoot out along the star’s axis of rotation. Some astronomers

claim Eta Carinae’s axis is not pointed in our direction. Hopefully

they’re right.

Best Regards,

Robert

March 26, 2013

Note: Previous newsletters can be found on my website

|