Gravity enables life. In a very sparse

cosmos, gravity gathers enough matter to form stars and planets. It

squeezes stars until they burst with the energy that supports life and

the atoms from which planets and people are made.

But gravity also destroys its own creations.

Astronomers often witness stars and

planets being eaten by bigger stars and by black holes. It’s cannibalism

on a cosmic scale, and not for the faint of heart.

A star like our Sun will burn steadily

for billions of years, providing a serene environment for its orbiting

planets. But, when such stars exhaust their thermonuclear fuels, they

shed their outer layers and their cores collapse to form White Dwarfs,

objects about the size of Earth but with masses comparable to our Sun.

That’s the fate of the least-massive 95% of all stars, including our

Sun. A single teaspoon of White Dwarf would “weigh” 30 tons. Gravity on

its surface could be up to one million times greater than on Earth, and

its surface temperature could be up to 250,000 °F, 25 times our Sun’s

current temperature.

Planets orbiting too close to these stars may be consumed.

Astronomers reported this month observing four White Dwarfs

that have planet guts running down their chins—spectral lines of iron,

nickel and sulfur, elements typically found not in stellar atmospheres

but in the cores of terrestrial planets like Earth. One of these stars

is now consuming an estimated one thousand tons of planet guts every second.

While iron and nickel may be tasty, they

are rare delicacies in our universe. Truly mammoth appetites require

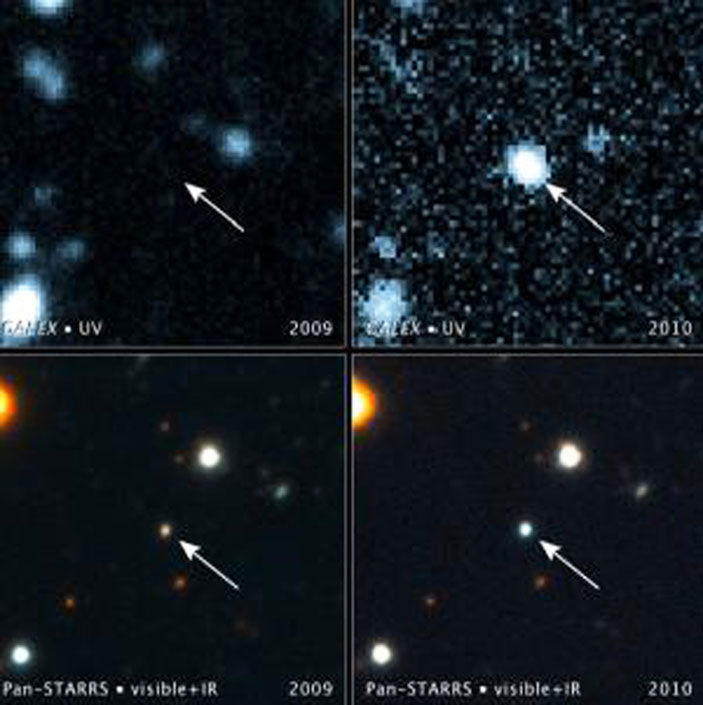

more readily available fare. How about helium? The images below show a

galaxy 2.7 billion light-years away (one light-year is six trillion

miles). The two images on the left were taken in 2009, just before

dinner, and the two images on the right are from 2010. The upper image

pair was taken in ultra-violet (UV) light and the lower pair in visible

light. The images show that the central black hole of this galaxy

consumed the helium core of a star. The image is brightest in UV because

the helium gas became very hot as it fell into the black hole at 20

million mph. Astronomers think we may be seeing the dessert course; the

star may have passed near the black hole many years ago when its

hydrogen gas was eaten during the entree course. Helium is heavier than

hydrogen, thus it sinks to the star’s center and is more tightly held.

The outer hydrogen layer is much easier for the black hole to strip off

and gulp down. The mass of this black hole is estimated to be three

million times our Sun’s mass.

Galaxy PS1-10jh: 2009 left, 2010 right, UV upper, optical lower

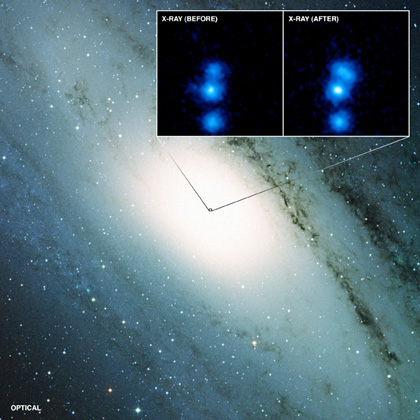

Below we see a visible light image of

Andromeda, our large neighboring galaxy also called M31. Inset are two

x-ray images of its core. In January 2006, x-ray emission from M31’s

central black hole increased one hundred-fold as it munched on some

delicacy, perhaps a giant gas cloud, a star, or just the odd planet.

M31, Andromeda Galaxy

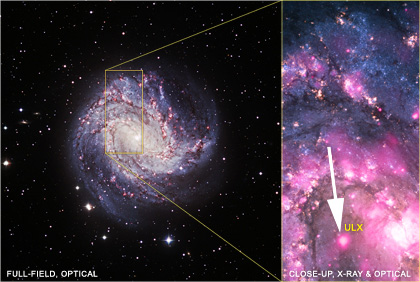

Finally, we have M83, a galaxy 15

million light-years away. It apparently has a mid-sized black hole of 40

to 100 solar masses in its spiral arms. X-ray emissions from that

location jumped 3000-fold in 2011, when it is thought to have consumed a

companion star.

M83

Yummy. What are you having for dinner?

Best Regards,

Robert

May 16th, 2012

Note: Previous newsletters can be found on my website.

|